Paul Thomas Anderson‘s Boogie Nights is a love-letter to the golden age of porn, tracing the phoenix rise and fall of fictional porn star Dirk Diggler played by Mark Wahlberg.

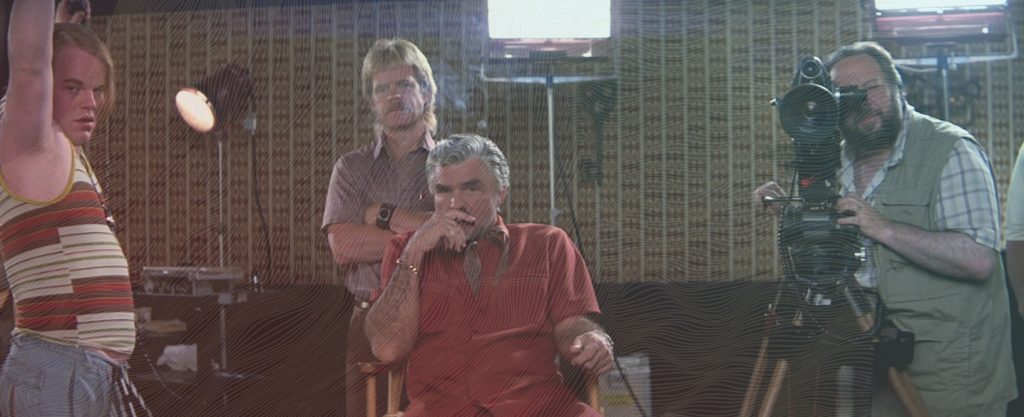

A kid with big dreams and a still bigger dick, battened down in flared jeans, 17-year-old Eddie is enfolded in the bosom of the San Fernando Valley of the ’70s. Under the watchful, papa’s eye of adult filmmaker Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds), he’s transformed into an overnight sensation, but is carried away in the counterpoint rhythms of a changing, non-familial America, fluffed to arousal for a new era where videotape replaces the reel; where appetites take their cue from amphetamines, waxing bigger, harder, faster, and the fashion is for quick fix, curb-crawler porn.

Boogie Nights is a film about desire, but, perhaps least of all, the desire that can be sated by a blue movie at the cinema. Anderson’s film is surprisingly soft on sex, never pulling focus on the real hot and heavy, and only once allowing us a glimpse of Eddie’s flesh tone gift — and only then in the dying minutes. The desires felt by the film’s ensemble are consistent and pure. Jack’s big dream is to slake but also to elevate the desires of his audience — to make a porno so good they’ll stick around to see the end of it after shooting their load. Leading lady Amber Waves (Julianne Moore) wants a reunion with her estranged son, and – supporting-star Buck (Don Cheadle) lives for the inaugural opening of Bucks Super Stereo World. Rollergirl (Heather Graham) wants a real mother, and Scotty (Philip Seymour Hoffman) wants Dirk.

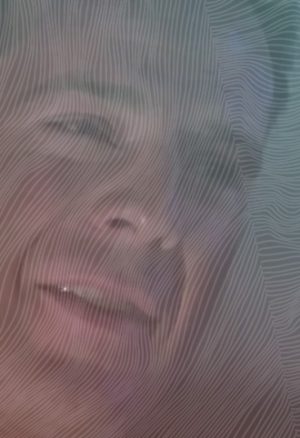

This single frame — tight on Eddie/Dirk — is taken from the film’s climactic pre-finale and is one of a series of close-ups designated to individual characters. Each close-up squares in on an expression — the sublimation of complex and incommunicable desire. Often far-off or trained on an (initially) off-screen object, it points toward something more than we, the audience, can physically see. Dirk’s close-up is the culmination of the above, and — unlike the others painfully decipherable. It comes within a section of the film subtitled ‘Long Way Down (One Last Thing)’, which sees a coke-gone Dirk, Todd and Reed attempting to sell half-a-key of baking soda to a wealthy LA party-boy. On stepping through the gate of Rahad’s condominium, with its rough stone cladding and hothouse plants, it’s clear they’re out of their depth — what with Rahad dressed in Y-fronts and shiny kimono, playing at The Deer Hunter with his prize silver pistol and grooving to ’80s chart classics while a Chinese rent-boy called Cosmo lights off fire crackers every few seconds. All the while, pacing back and forth is a huge black guy with a Luger beneath his blouson jacket.

Then, in the pandemonium, a momentary quiet: quiet, but for Rahad’s homemade mix-tape, playing the opening bars of the pop hit ‘Jessie’s Girl’. Anderson’s film is full of music—anthemic, diegetic dance numbers — but for the first time we pay heed to the lyrics, because Dirk is listening. The camera settles on his face and holds there for almost a minute. In the overarching context of Anderson’s style of shooting — favouring long pans and scouring single-takes — it stands out. His features look as if they’re being pulled by invisible thread, twitching with immiscible thought and feeling, refusing to solder into a single, solvent, clarified look. Vocalist Rick Springfield sings the high-planing refrain: “Why can’t I find a woman like that?… Like Jessie’s girl?”

And we know what Dirk is thinking: how, in coming all this way, is he still so far behind?

Jack’s world had seemed airtight, a cosy cornucopia, benevolent in its provision of a surrogate family: a prelapsarian Eden (with pool) for anyone who never had what they needed. In fact, this world has already proven permeable to prejudice, corruption, suicide and murder. Lost to Dirk is Springfield’s world of provincial dilemmas; the crush at the soda fountain; and innocent lovemaking between two ordinary people who are hot for each other. The perversity of pornography has made him old before his time. All this made stark as day by a guitar riff and Rick’s raconteur — just a guy with a hard on for his best friend’s chick.