We’re six minutes into Martin Scorsese’s rapturously nasty remake of Cape Fear, and the first taunt that De Niro’s just-out-of-jail Max Cady visits on the Bowden family, assaulting them with a foul miasma of cigar smoke and menacing guffaws, is to seriously mar their viewing of the film Problem Child. That’s the film playing in the dark, and it’s the Bowdens’ stricken point of view we’re given.

On a typical movie night in August 1990, Nick Nolte’s Sam, Jessica Lange’s Leigh and Juliette Lewis’ Danielle could have had a choice of Ghost (apt), Presumed Innocent (way too close to the bone) or Die Hard 2 (no one dies harder than Max Cady). Who, with a 15-year-old daughter, would have chosen Problem Child? Turning up blind, as one guesses they have, it’s their one option for a comedy, unless you count Duck Tales: the Movie, and this tense, mutually resentful family are in dire need of nothing if not some laughs.

What they get are De Niro’s laughs, which sound like they’re coming from a particularly sarcastic circle of hell. They don’t know it yet, but the film-within-the-film obliquely foreshadows their coming ordeal, too. John Ritter is wading through the wreckage of his home on screen, trying to make sense of Junior: why’s he acting out? What did Ritter ever do wrong as a father? When Sam took on illiterate Max as a public defender, he betrayed his client’s trust by hiding a document that might have got him acquitted. Max, who’s decided to make Sam’s life hell in revenge, is basically his Problem Child.

“When Cape Fear was released in 1991, it was dismissed in some quarters as little more than an A-list Freddy Krueger movie”

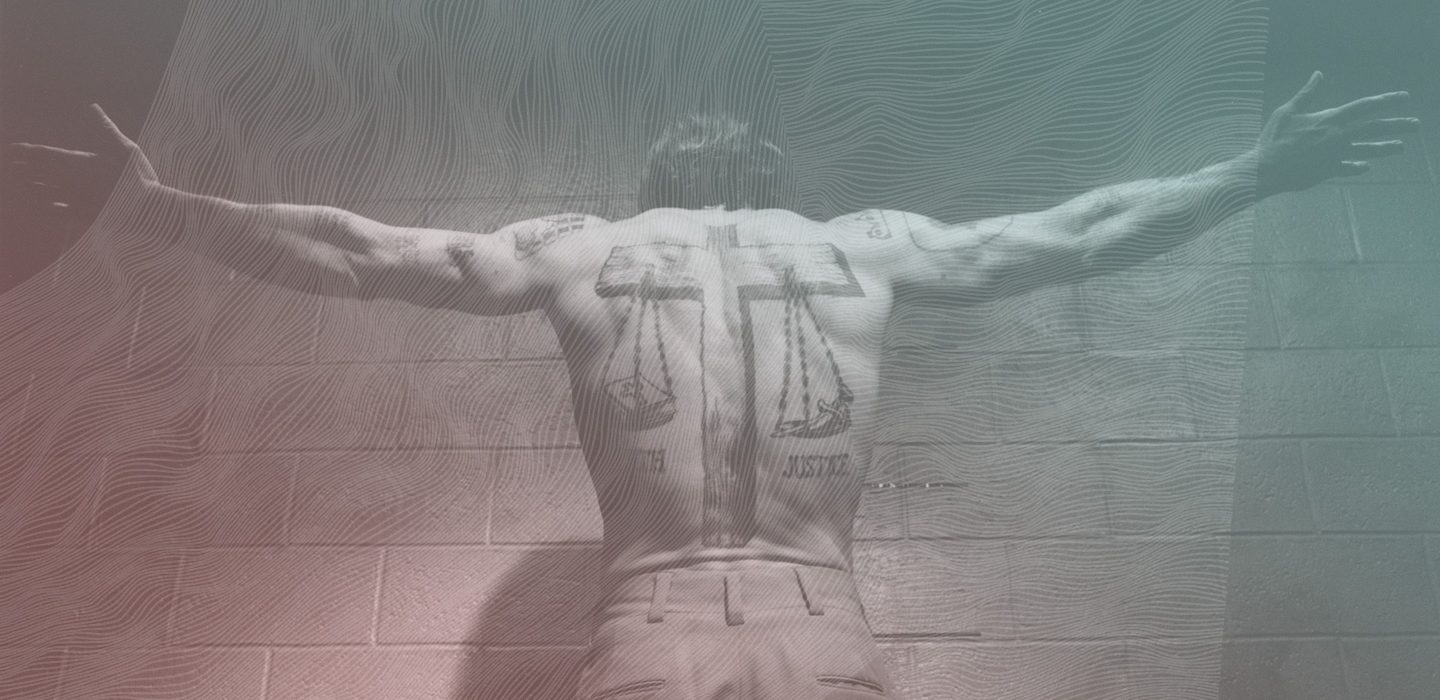

Cady’s original crime was molesting a teenage girl, as he will do later with Danielle, in the bravest and most revelatory scene of Lewis’ burgeoning career. Look at how the cigar-lighting here — his fat, ostentatious puffs — establishes an oral fixation. The glowing nipples on his tatty novelty lighter are perfectly turned so that the Bowden clan, sitting behind, can see them light up. To own such an object is to have a fairly clear opinion of women and what they’re good for, as Illeana Douglas’s character will also horribly discover. The parallel scene in the school auditorium will involve Max’s thumb, not a cigar, but neither image is exactly disguising what he wants to put where. Note, also, that both De Niro’s thumbs are in this shot, and one is doing to the fighter what he’ll more or less do to Danielle.

When Cape Fear was released in 1991, it was dismissed in some quarters as little more than an A-list Freddy Krueger movie — funnily enough, the screenwriter, Wesley Strick, would go on to write the (terrible) remake of A Nightmare on Elm Street It’s hardly such a galling analogy when you consider Wes Craven’s own skilled way with symbolism. Cady is a similarly ghastly apparition, a monster of the underclass — and let’s not forget that both are child molesters, victims of a fatal lynching in one case and a deliberate miscarriage of justice on the other. They’re cousins in infernal retribution: between them they’ve got the dreamworld and the daylight covered.

To accuse Scorsese of stooping to genre is to make the snobbish assumption that genre is beneath him, when he’s actually working it from the inside: this may have been the biggest budget he’d enjoyed at the time, but until the houseboat showdown he’s using it to goose our expectations, not kowtow to them. He says things about the Bowdens — about their money and hypocrisy, and fundamental unhappiness — that J Lee Thompson’s already-forceful 1962 version, with indignant patriarch Gregory Peck pulling up the drawbridge, wouldn’t dare. And he goes to town with the sheer, insinuating concentration of his imagery. This shot is a manifesto on Cady’s behalf: it’s saying to the Bowdens, “I’m going to screw with you, until you scream or die, in these exact ways. Because this is who I am.”