A complete insight into one of the greatest directors of our time, Terrence Malick. As vast, delicate and precious we could.

By A. Woodward, D. Jenkins, M. Conteryo, C Marley. via LWL.

Many of Malick’s titles are available on Criterion. And on various torrent and streaming sites. So before we continue into Malick’s films – No torrent, magnet link or stream will do his titles justice. Please consider buying the physical copies of Criterion Collection’s BluRays.

Index

- Badlands

- Days of Heaven

- The Thin Red Line

- The New World

- The Tree of Life

- To The Wonder

- Knight of Cups

- Voyage of Time

- Song to Song

- A Hidden Life

Badlands

“He was handsomer than anybody I’d ever met. He looked just like James Dean.”

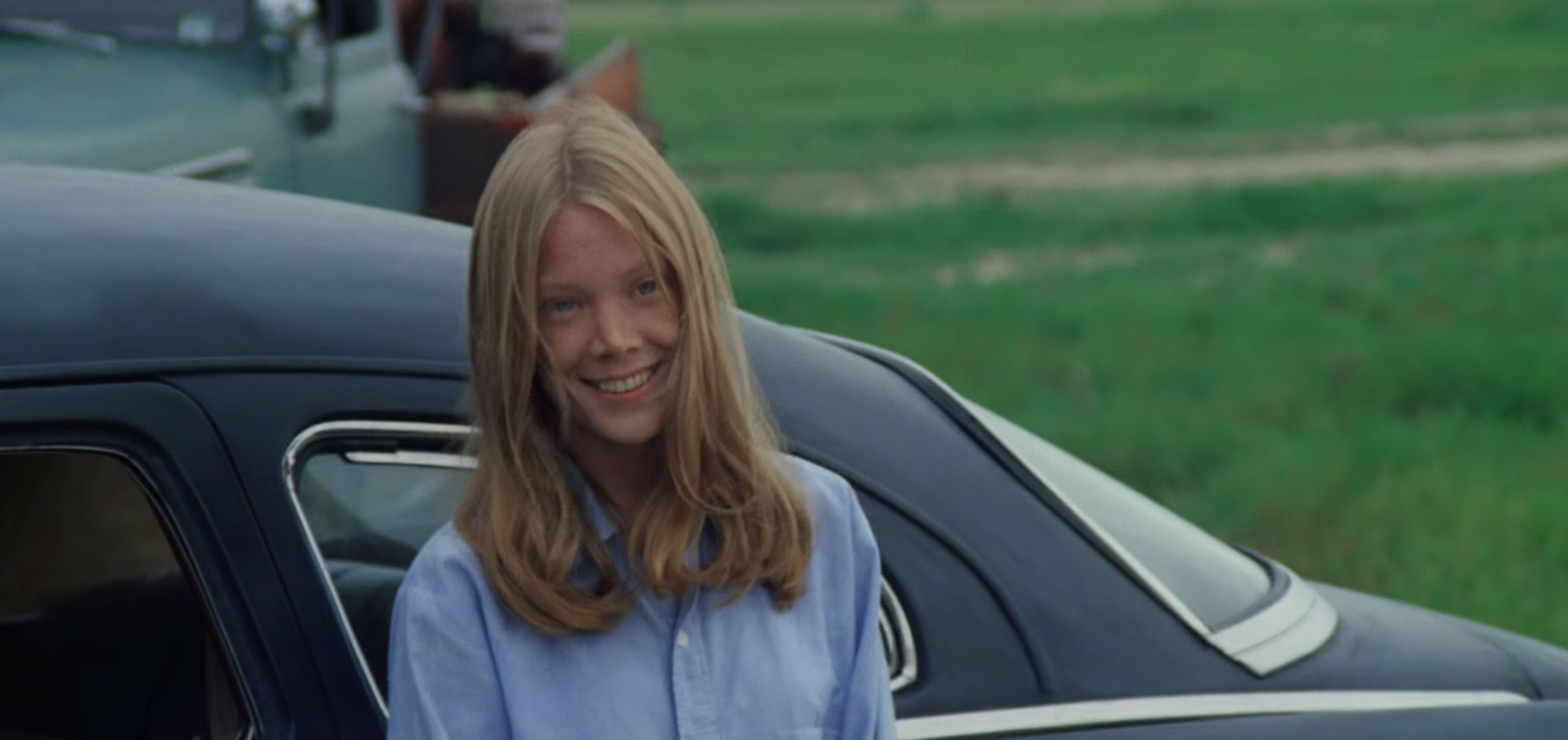

To 15-year-old Holly Sargis (Sissy Spacek), the sun rises and sets on Kit Carruthers (Martin Sheen). He’s a misfit, a 25-year-old garbage collector with an abundance of peculiarities, delusions of grandeur, and no moral compass. And he does, indeed, look like James Dean.

Terrence Malick‘s 1973 directorial debut. Badlands, begins in 1959, four years after Dean was tragically killed in a car accident. Though the young star is dead, his legacy looms large. Through Dean’s few but significant roles, his image as a symbol of teenage restlessness and disillusionment was cultivated both by Hollywood and the public. Dean’s sudden death encased him in his own mythology – forever young, a rebel eternally in search of a cause.

In Fort Dupree, South Dakota, a small town far removed in both distance and noteworthiness from the stretch of highway in California where Dean lost his life, Kit seeks to emulate the icon. When Holly’s father makes it clear that he disapproves of Kit’s relationship with his daughter, Kit shoots the man and the lovers embark across America’s heartland on a killing spree inspired by the true crimes of Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate in 1958. While on the run, Kit maintains a degree of aloofness, but Malick repeatedly exposes the performativity behind his anti-hero’s devil-may-care attitude and his appropriation of Dean’s persona as a means to become (in)famous.

While Kit and Holly are making their way west towards Montana, Kit suggests they change their names and become James and Priscilla. The intended homage on his part is obvious, so obvious that it’s painfully uninventive. Kit models himself on Dean, wearing the right jeans and combing his hair the right way, but it’s never more than an imitation with no creativity or originality behind it.

In addition to undermining Kit’s emulation of the star, Malick draws attention to the hollowness of this iconography in the first place. In his three starring roles – in Elia Kazan’s East of Eden, Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause, and George Stevens’s Giant– Dean plays young men struggling to find their place in the world they’ve inherited from distant and inadequate father figures; they contend with grief, grudges, and bitterness; they grapple with relationships and the complexities of personal identity. The three vastly different characters are united by Dean’s performance style, which imbues empathy into what are essentially stories of lost boys.

Kit’s imitation scratches the surface of the star. He styles his hair and adopts certain mannerisms, but never interrogates the star persona in a significant way. There’s more to Dean than the superficial aspects, but these elements are what have been foregrounded in his iconography and they are what Kit latches onto.

When Kit is apprehended, he marks the location with a small rock pile at the side of the road where he was caught. It’s a gesture that harkens to the memorials constructed for Dean and others who die in car accidents, a commemoration of their last moments. In Kit’s instance, this action is both selfish and empty. Malick lays bare the degree to which Kit is desperate for recognition and to be of interest to someone else, so much so that he’ll make a last- ditch effort to build a monument to himself before he’s dragged away in handcuffs.

When he’s arrested, an officer comments that Kit looks like Dean. Malick’s camera lingers on Kit’s response and the genius of Sheen’s performance shines through. Kit smiles in a way he hasn’t before; he’s genuinely touched by the comparison and reacts bashfully to the remark. To Kit, looking like Dean means he’s interesting and worthy of notoriety. For a man otherwise empty, this is the highest compliment he can receive.

Malick carefully scrutinises the ways that police and others who interact with Kit are either charmed by him or willing to humour him. In his own twisted way, Kit aspires to the kind of recognition that comes with fame, but the only way he knows how to get there is through hollow imitations, violent crimes, and empty gestures. Malick sees through all of those aspirations and reminds us of Kit’s desperation and insincerity. Kit is ultimately a footnote in James Dean’s mythology; a minuscule pile of rocks on the side of the road in the vast badlands of Montana

Days of Heaven

“Me and my brother, it just used to be me and my brother. We used to do things together. We used to have fun.”

In Days of Heaven, you hear Linda Manz before you see her. Or, at least, that’s how it seems. In the opening credits, director Terrence Malick offers us his time-travelling machine by way of a slideshow: black-and-white photographs of doleful turn-of-the-century figures, of all ages. A grubby-faced young girl is the final image and our gateway to the film’s main story. But this photograph, actually the striking, wise face of actress Linda Manz, just play-acts history. Besides, it’s the arrival of her voice, not her face, that holds the key to this strange, earthy, yet ethereal film.

Malick’s second feature is set in America in the early 20th century, telling the story of Bill (Richard Gere) and Abby (Brooke Adams), a young couple who pretend, when asked, that they are brother and sister. In the film’s opening, they flee the harsh industrial doldrums of Chicago following a violent altercation to find farm work in the Texas Panhandle. Accompanying them is Bill’s actual, younger sister Linda, played by Manz. When the terminally ill, rich farmer (played by Sam Shephard) falls in (ove with Abby, the couple decide she should accept his marriage proposal and see if it offers them a way out of their sorry lot in life. By the time Manz tells us what we already know – “She loves the farmer” – the burning denouement to the love triangle has been sparked. From the off, Manz s own voice guides us, in voiceover form. Hypnotic and heavily accented, her 15-year-old’s abrasive tones temper what could potentially feel melodramatic; guiding us along the plot with its ebbs and flows, even its stutters and pauses.

But the voiceover is more than just Manz’s voice – its her perspective; not only how she speaks, but what she says. Days of Heaven was never meant to have a voiceover at all. If you look at the original script, you’ll see it barely resembles the finished product. It was when experimenting with the idea of adding a voiceover from Manzs character, that Malick and his editor Billy Weber landed on a solution: instead of giving her lines to read, they would ask Manz to look at the scene and simply tell them what she saw. The resulting voiceover, which combines her instinctive reactions, in concert with some of Malick’s input, might be the first time a teenage girl s actual point of view was committed to celluloid, ever.

On the cusp of fully understanding what she is commentating on, Manz somehow knows more than any of us. Fifteen going on 50, her instinctive musings are enough to make you shiver (“Sometimes I feel very old, like my whole life is over. Like I’m not around no more,” she says at one point). She also knows when to be quiet. Her long, solemn face, jutting its chin and widening its eyes at the world Malick has conjured, stays with you. It’s a voiceover that feels secret, like it’s being overheard. She brings you close – very close — to the lives of these unfortunate .characters, just like her character cups her ear to the American earth, listening for what lies underneath.

You can see the prototype of Manz’s commentary in Badlands, in which Holly (Sissy Spacek) narrates the story of her relationship and brief life of murderous crime on the road with Kit (Martin Sheen) in similar lyrical fashion. Holly’s voiceover, according to Weber, was meant to sound like a romance magazine; deliberately artificial and naive; rather than striving for the grit of what Manz eventually delivered.

But with the final product relying so much on the unfiltered musings of a streetwise young girl, it’s a trick that probably couldn’t be repeated. Manz herself grew out of the position she had carved for herself in celluloid, eventually leaving behind auteurs like Dennis Hopper (she starred as punk heroine Cebe in his controversial Out of the Blue in 1980) to retire and start a family (with a cameo in Harmony Korine’s Gummo, in 1997). In a rare interview in Time Out in that year, she simply said how she had been left behind in the milieu of new actors she came up alongside. “So I laid back and had three kids. Now I enjoy just staying home and cooking soup.”

When does a single voice set the tone, in any film? Tone is slippery: it evokes atmosphere but also musicality, where a single note can change how the whole resonates, forever. It makes sense, then, that ‘tone’ comes from the Greek ‘tonos’, for ‘tension’. Malick is a filmmaker who thrives on tension: between the before and after, and between what nature observes and the philosophical ointment he has the power to apply afterwards. Here, Manz’s voiceover is a formula as magic as the hour at which Malick chose to film Days of Heaven.

The Thin Red Line

Terrence Malick’s 1998 film The Thin Red Line begins with a shot of a crocodile slowly submerging its sizeable girth into a waterhole choked with vibrant green duckweed. As the croc disappears from view, birdsong of the jungle is drowned out by Hans Zimmer’s swelling score. The film closes, after we see battered and beleaguered soldiers being evacuated off Guadalcanal island, with a serene vision of a beach at low tide. In the foreground, slightly to the right of centre frame, is a bit of flotsam washed up; a fragile-looking plant with its roots exposed.

The film is based on the 1962 novel by James Jones, a fictionalised retelling of the notoriously bloody Guadalcanal campaign which took place in 1942 and ran over into 1943. It sees US infantry division, Charlie Company, tasked with retaking an airfield and supply depot from the Japanese. Curiously, Malick’s third feature is bookended with images of the natural world and these first and last shots are entirely devoid of human figures.

This reworking of the World War Two genre takes into account nature’s defilement and debasement at the hands of men in the theatre of war. A hill which, outside the conflict, would be of little importance, becomes a heavily fortified battleground, something to take by any means necessary. Lives are sacrificed. The soil is tainted by human blood.

“The Thin Red Line is an environmental disaster movie in army fatigues”

The director sets a challenge to the viewer: we are asked to contemplate the film’s tragic imagery as related to our collective disconnectedness from nature. In Malick’s hands, the war film is a springboard for musings on how technology corrupts and pollutes pristine spaces. The Thin Red Line is an environmental disaster movie in army fatigues. Repeated shots of radiant sunshine streaming down through lush treetops, tall grass swaying gently in the breeze, sun-dappled rivers glistening, primordial mangrove forests and vistas of undulating hillsides are not randomly inserted pretty pictures offering momentary respite from the bursts of horror. They are fundamental to the meaning of the text. Malick gives nature a voice. We should feel these images as deeply as the miseries endured by the soldiers.

A grey battleship docked in a bay, at dusk, spewing black plumes of smoke into the air; a baby bird with a broken wing struggling to stand up; two batteries of 105s slamming shells into a ridge at dawn, and the awful sight of a crocodile taken hostage by bored soldiers on R&R. Tied up and looking glum on the back of a wagon, a soldier prods it to goad a response. A focus on the damage inflicted against wildlife is perhaps intended by Malick as his version of gore shots and a statement on the environmental obscenities which occur in wartime.

“I’ve seen another world. Sometimes I think it’s just my imagination,”

We give everything in the world its frame of reference, and so the mistake we make is believing everything exists exclusively for us. Over time, we have become destructively set apart from the majesty of creation. That’s why The Thin Red Line commences proper when Private Witt (Jim Caviezel) goes AWOL and lays low among the members of a Melanesian tribe in a coastal village. Witt is a spiritual guy attuned and appreciative of nature and its inherent wonders. He represents hope and optimism. Both Witt and his chief antagonist, Sgt Welsh (Sean Penn), an embittered existentialist, articulate their positions throughout. These face-on-face generate a great deal of thematic tension, as one crunches against the other like tectonic plates. Witt is seen as the redneck oddball of C Company, a “magician” as his commander sarcastically calls him, yet his eyes are wide open to his surroundings. “I’ve seen another world. Sometimes I think it’s just my imagination,” says Witt. Welsh the cynic later retorts, during what turns out to be the pair’s last encounter: “There’s not some other world out there, where everything is gonna be okay. There’s just this rock.”

There is just this rock floating in space, but the other world, though hidden by our disconnectedness, is all around us, we just need to find the path again, to re-engage. The Thin Red Line offers an engrossing, deeply poetic investigation into humankind’s angst and search for meaning in a poisoned environment. Malick calls philosophical and spiritual awareness in his film ‘the spark’.

It resides in all of us, whether we recognise it or not. Even in characters such as Sgt Welsh or the tyrannical Lt Col Tall (Nick Nolte). The spark is light and light is the truth leading us to salvation and reconnect with our world. Like Witt, we will then be able to see all things shining.

As a side note, it should be mentioned that the Criterion edition of this film is excellent, and no standard SD torrent version does this film justice.

The New World

Before his 21st century turn towards contemporary subjects and settings with To the Wonder (2012) Terrence Malick had always been a historical filmmaker, albeit a singular and unusual one, less interested in the hard facts than in mapping a series of sensations across time. The impulse for impressionistic re-creation was present all the way back in Badlands (1973), with its grimly lyrical allusions to the Starkweather-Fugate murders, as well as in the near-surrealist Dust Bowl imagery of Days of Heaven (1978), including a swarm of locusts seemingly unleashed direct from the Book of Exodus. In The Thin Red Line (1998), the Pacific Theatre is conjured up only to be filmed as a despoiled Paradise wholly out of time. With The Tree of Life (2011), the director audaciously conflated his own mid-20th century autobiography with the Big Bang, resulting in concentric origin stories juxtaposing the intimately lived-in with forbidding galactic abstractions.

“Malick cultivates a beguiling blend of stylisation and fidelity”

Malick’s superlative fourth feature, 2005’s The New World, is structured around the grandest and most problematic of foundational American fables: the story of Pocahontas, the young indigenous princess who fell in love with a European adventurer, supposedly sparing his life and setting the stage for a harmonious co-existence on both a micro and macro level. The myth’s enduring resonance lies not only in its irresistible cross-cultural romance and attendant metaphor, but how it sanitises the reality of conquest (and genocide) through the flattering figure of a “Good Indian” literally welcoming her Christian lover-slash- savior with open arms. As a filmmaker of faith, Malick could easily have capitulated to the master narrative and its subtext of civilization-through-conversion, but opts instead for a bracing defamiliarisation that reconfigures the story’s deeper meanings as thoroughly as his destabilising compositions and elliptical editing rhythms ripple its surfaces.

The movie opens with a view seen through water: up is down, the sky reflected in the Atlantic ocean. The camera is more mesmerised by the elements than the men descending from ships anchored offshore and rowing towards land. Beauty exists here independent of the sailors’ impending “discoveries,” and is momentous in and of itself, beyond the breathless impressions of the invaders or even the hushed, grateful invocations of the “naturals” living in the forests.

One way to describe Malick’s cinema is to say that it’s caught between imminence and immanence: his films are made up of moments in which we can sense something is about to happen and yet which already feel fully inhabited by some larger presence. And so it goes here as well. Nothing is being discovered, only revealed: the “new” world is very very old.

As in his earlier period pieces, Malick cultivates a beguiling blend of stylisation and fidelity. By casting the 14-year-old Q’orianka Kilcher as Pocahontas (never named in the film) opposite 30-year-old Colin Farrell, the film not only honours the historical record but infuses the frolicking of its central couple with the threat of taboo – their coupling, rendered as gesturally as the director’s other romances, plays less as boy-meets-girl than innocence-meets-experience. And by reproducing the Jamestown settlement through the lens of authentic squalor, Malick undermines the idea that the newcomers are bringing much of value to their new surroundings: in a film defined by an all-encompassing gorgeousness, the British attempt at remaking the land in their own image represents a form of show-stopping ugliness.

The Tree of Life

In 2011, shortly after I attempted suicide and was diagnosed with major depression disorder (MDD), I bought a pirated copy of The Tree of Life from a guy who told me it was “a great nature documentary.” He said, “The director is American, he is very famous!” And I, a Turkish teen who loved American cinema, thought a nature documentary was just the thing to help me at that moment. I sat down to watch the film with my mother, who had decided she had to monitor every film I watched to make sure I didn’t see anything that depicted suicide or death. She gave up fifteen minutes in. I didn’t.

Up until that point in my life, I had never seen a film like The Tree of Life. I didn’t realise that a non-linear narrative achieved through the intuitive juxtaposition of images was possible. But what captivated me most was the sense of grief that loomed over the film. Grief not just for the dead, but something else that I didn’t have the words to describe.

When Mrs O’Brien (Jessica Chastain) repeated the first words of the prologue, “Where were you?,” anger replaced my feeling of wonder. I asked myself the same question again and again for months, directed not just to God but to anyone who did not see how much I was suffering. It became the defining question of the film for me. The question was filled with anger, desperation and the kind of sorrow that sits on your chest and refuses to let go. All those emotions took over my body and ruined happy moments with their sudden appearance. They all manifested in the film for me, and defined it for years to come. Then I rewatched it again in 2019.

MDD is a lifelong illness. It has no cure. You can treat the symptoms with medication, or whatever you choose that works for you. The treatment of symptoms (which include anxiety, sadness, insomnia, mood swings, and more) is not always successful but it can make your life more manageable. It can take years for a patient to find the right medicine, and those years can be filled with sadness and the feeling of missing out on your own life. They are years that are forever lost to you. You are, or at least I am, forever grieving the person you could’ve become if you didn’t have this illness. Grief and loss has, and always will, loom over my life. For the longest time, anger had resided with them. Anger that made me ask, “Where were you?” It took me almost 10 years to come to terms with it and replace the anger with acceptance, and more importantly, peace.

In the spring of 2019, shortly after I came close to attempting suicide once again, my psychiatrist asked me to trace my illness from its beginning to now. Most importantly, she wanted me to trace how I made peace with myself and with the world. I knew one of the best ways to do it was through watching films — my one passion that even depression couldn’t take away. It took some time to figure out, but all doors eventually led to The Tree of Life, to that haunting sense of grief and loss.

“I saw the movement of time not just as nonlinear, but as many circles, some of them interconnected, some leaving and returning to the film to finish their circle”

It felt like I was watching a completely different film to the one I watched as a teen. It wasn’t that the grief and loss were gone, but this time they were holding hands with peace and acceptance, instead of anger and resentment. The emotional evolution of the film has resonated with the perception I have of my illness in a way I hadn’t ever considered. I saw the movement of time not just as nonlinear, but as many circles, some of them interconnected, some leaving and returning to the film to finish their circle, and some never seen again, finishing their journey not on screen, but left hovering on the viewer’s mind to finish on their own.

The film that once seeded anger in me turned into an embrace of loss. The defining moment of the film moved from “Where were you?” to “Help each other. Love everyone. Every leaf. Every ray of light. Forgive.” It opened my eyes to how essential loss and grief are not just to human life, but the life of every living being.

The Tree of Life takes sorrow and through leaves, light and dinosaurs, it gave back to me the impossibility of living without accepting grief as an unwavering stream that runs through all our lives, whether it be for a dead son or an illness that will never abate. And with that acceptance comes happiness, and peace in an endless white land where everything and everyone lost come together.

Side note: The Criterion version has a re-cut Malick version released in 2019. While getting the BluRay is your best option, should you decide to pirate the film, make sure you download the correct version.

To The Wonder

We’re stuck in the middle. The starry skies above us, the barren earth beneath. Raise one arm to sense the divine, lower the other to feel the ground’s emptiness. Make yourself a channel of love and submit to its will.

2012’s To the Wonder is Malick’s greatest celebration of bodily movement. The ballet-trained Olga Kurylenko lends a weightless quality to Marina, her persona comes close to realising the Whirling Dervish ideal. She blossoms in Oklahoma as a French- Ukrainian outsider when her love for Ben Affleck’s Neil is pure. She pirouettes in the grasslands, but we gradually see her freedom suppressed by her partner’s stillness. He is a masculine monolith aptly represented by the ever-unmoved Affleck. Mirroring John Smith lifting Pocahontas out of the forest and into the frenzied streets of London in The New World, Malick revisits the age-old tale of feminine innocents confronted by destructive masculinity in the present day.

The recurring tenet of Malick’s oeuvre is the realness of our encounter with the sublime through the mundane – golden beams slipping through net curtains, still sheens balanced on a stream. He combines Martin Heidegger’s concept of the World as Being with the fideist duty of love propagated by Soren Kierkegaard to show that Marina moves not by choice, but by a necessity to act as a medium between the earthly and the divine. Kurylenko embodies these concepts as she spirals into the horizon, while Affleck shuffles along silently behind her. Affleck has said that he read Malick’s own translation of Heidegger’s ‘The Essence of Reason’ to gain some insight before filming. He said it gave him none.

While most of the film was unscripted, it is no accident that the film starts with the couple visiting Mont Saint-Michel, known as La Merveille, the titular ‘wonder’. The towering monastery is a physical stand-in for ‘the ladder of love’ in Plato’s ‘Symposium’, taking us toward higher knowledge. At the summit sits a garden, the Eden from which our central couple will fall and spend the rest of the film struggling to confess to Javier Bardem’s Father Quintana. The ascent/descent is not straightforward, depicting the climb to love as an uneven spiral staircase. It is, as Malick referred to the film before choosing a title, “radiant zigzag becoming.”

“I write on water what I dare not say”

Marina is never damned for her failures. She receives full redemption as she moves toward self-fulfilment. She dances when she cannot speak, delivering most of her lines through voiceover, and thus movement becomes her language. While swimming, she says, “I write on water what I dare not say”, inviting us to read her gestures. She is caught between spaces, between her European homeland and Neil s American wilderness, who in turn struggles to negotiate his desires both for Marina and the rancher Jane, played by Rachel McAdams.

The possibility of loving multiple people is explored in Song to Song, as Rooney Mara’s Faye balances a ménage a trois with Michael Fassbender and Ryan Gosling. The lovers wheel together in an unpredictable ballet, bouncing off one another, often into the arms of a secondary Natalie Portman or Cate Blanchett, before being drawn back into orbit. Malick does not depict polygamy without rupture, quite the opposite, but he does acknowledge the unavoidable interaction of human bodies through erotic desire, and that in twirling, there will be inevitable moments of collision.

Malick often presents his actors with a reading list rather than a formal script. Among the material for Marina was ‘Anna Karenina’ by Leo Tolstoy, an epic of Russian literature about the heroine’s part in a love triangle and her eventual suicide. Kurylenko has revealed that she shot three or four alternative endings for To the Wonder, and her death may have featured among them. However, while the film’s non-linearity makes us question the temporal location of the conclusion, it appears to be optimistic.

Having divorced Neil, Marina finds herself in a woodland after rainfall, stumbling out into a field and turning towards the sun, its light shining directly onto her face. In voiceover, she whispers, “Love that loves us… thank you,” and we see Mont Saint-Michel one last time before the screen fades to black. For all her miserable toing-and-froing, Marina has spun out of the woods and into plein air, twirling to the Wonder. We’ve been here before, but this time our perspective is different – as Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, “nothing, and yet everything, has changed.”

Side note: Make sure watch the making of on YouTube.

Knight of Cups

Although many critics may think they have his style pegged down, Terrence Malick constantly proves himself to be an evolving, formally adventurous filmmaker who resists easy categorisation. Up until 2011 ‘s The Tree of Life, there was a fixed idea of what we may expect from a Malick film: a period setting; an epically-scaled narrative told through impressionistic montage; a sustained study of man’s relationship with the natural world. When Malick first set his camera on the contemporary world in The Tree of Life it was undeniably jarring – the director’s ethereal style seemed an odd match for the ultra-modern, post-industrial cityscape through which the adult Jack (Sean Penn) drifts. Camera moves familiar from the director’s earlier films reappear, but now with different connotations: a low-angle shot of a skyscraper reaching towards the sky is a direct parallel to the final image of The New World, but in that film a tree acts as a bridge between the tangible world and the heavens. Here, the image of the monolithic building is cold and foreboding.

“if they reject the land, the land rejects them in turn – and this rejection is experienced as a profound existential emptiness”

In Malick’s cinema, nature functions as a material expression of the divine and a gateway to metaphysical transcendence. Yet, his characters consistently make the mistake of claiming ownership over nature. They sap its inherent power by transforming it into a commodity to be bought or sold. In Days of Heaven, Bill (Richard Gere) and Abby (Brook Adams) fall from grace by hatching a plan to steal land which, in actuality, belongs to no one; The Thin Red Line stages a battle over ownership of an island in the South Pacific as a living hell; in The New World, the actions of British colonisers leads to a horrific territorial war. If a character is willing to respect and nurture the natural world, it provides the path to spiritual fulfilment. But if they reject the land, the land rejects them in turn – and this rejection is experienced as a profound existential emptiness.

Such is the malady which haunts Jack, who glumly floats through the cages of steel and glass which circumscribe his daily life. His gaze is drawn to the small traces of the natural world which dot his workspace: a row of potted plants; a water fountain; a flock of birds mysteriously circling a tall tower. Instead of providing solace they merely accentuate how far removed this man-made milieu is from the organic environment. Malick’s most complete formal exploration of urban alienation, however, is 2016’s Knight of Cups, which explores the spiritual crisis of Rick (Christian Bale) an obscenely wealthy movie scriptwriter who struggles to reconcile his addiction to hedonistic pleasure with his desire to connect with something greater than the material world.

“The film has become known for its depiction of the high life, but it is also littered with shots of the homeless, dilapidated neighbourhoods, and abandoned businesses”

The cityscapes in Knight of Cups are in relentless motion, total transparency and constant stimulation. Images of transit abound: Rick speeding through the freeways of the city in his convertible; first-person tracking shots along subway tracks; commercial jets powering through the sky above. Whereas The Tree of Life’s Jack feels nothing but suffocation within his urban surroundings, Rick is more ambivalent. He registers an attraction to the thrills of the city, from the rhythmic strobe lights of nightclubs to the ornate foyers of five-star hotels; he simultaneously acknowledges the true cost of this luxury. The film has become known for its depiction of the high life, but it is also littered with shots of the homeless, dilapidated neighbourhoods, and abandoned businesses.

Recurring images of the ocean and distant mountainous regions serve as a reminder of the breath-taking majesty of the landscape. The land itself remains eternal, while the ephemeral man-made structures which sit atop it are in a constant state of flux, transforming alongside cycles of fashion and technological development. Existing alongside these, however, are images of nature as it has been commodified and vulgarised by the forces of capitalism which shape a technocratic consumer society. A striking image of the sunset is revealed to be a billboard, while the actual night sky is obscured by artificial lights. An aquarium filled with plastic replicas of naturally occurring phenomena is a caricature of authentic marine life.

Natural beauty is sublime because it resists all attempts to capture and contain its aura; as such, the manufactured simulacra in Rick’s world cannot satisfy his needs, they only exacerbate them. The fact that Rick, unlike Jack, is never able to fulfil his desire to connect with the unmediated world and quench his sense of longing makes Knight of Cups, in its own unconventional way, Malick’s most tragic film.

Voyage of Time

My mother-in-law loves to watch nature documentaries on TV. and does so when she comes over to stay. I’ll often lift a beady eye up from my laptop, especially when there are otters in the mix. But in the main, these types of mass-audience mature films irk me. Planet Earth, the BBC’s tentpole series narrated awed tones by David Attenborough, is a key offender, as its modus operandi is to build engagement with its spectacular images of wildlife through comparing the social rituals of animals to those of nor mat human beings. Cheetahs are referred to as boyfriend and girlfriend. Insects breakdance on the branch of a tree. Sloths engage ‘ a protracted domestic while they just… dangle there.

It’s the notion that these species can only be of interest if they’re shown as being somehow relative to the daily trials of our own tragically mundane fives that irritates. Terrence Malick’s 2017 film Voyage of Time offers a tonic for such anthropomorphised shenanigans by reenergising the hackneyed old conventions of the nature documentary. Through crisp, purposeful montage, it showcases the wonderment of this old rock while allowing the viewer to build their own profiles of the flora and fauna on screen.

Its most radical innovation is in creating an elegiac disconnect between image and narration. Instead of the classic commentary, whereby a plucky naturalist or biologist will take an educated part as to what’s occurring on screen. Voyage of Time (in its full-blown feature length cut, as opposed to the truncated, Brad Pitt-narrated version produced for IMAX screens), boasts a breathy lyrical narration by Cate Blanchett which seeks to tap into something essential that not only enhances the interpretive richness of the images, but forges a poetic connection between them as well.

Malick’s film is a fascinating study of procreation as the one truly spiritual act, and it makes a case for the rationalist belief in evolution, but leaves a tantalising amount of wiggle room for the conviction that there absolutely must be some nebulous divine power governing the course of creation. We’re never going to agree on who or what originated the universe as we now know it. More than that, we’re never going to have a definitive answer to the ultimate question that has dogged mankind since its earliest days. Why, then, not accept a combination of these two routes? Per The Tree of Life, the way of nature and the way of grace. “Mother!” is the constant refrain in the voiceover, and it speaks to the notion of all living organisms taking on a gender-aligned responsibility for multiplying their own species, which in turn fuels the raging fires of evolution. This is the story of how expelling matter from your body – be you an aardvark, a daffodil or a volcano – is the ultimate tie that binds us.

Instead of attempting to domesticate and catalogue all the elemental particles, single cell lifeforms and furry critters of the galaxy. Voyage of Time employs them as details in a broader cosmic tapestry. Many have argued that, with his return to filmmaking in 1998 with The Thin Red Line. Malick pointedly embraced a more experimental, more fluid mode of visual storytelling. This film arguably stands as the apex of that gradual shift, and unlike a regular nature documentary, it requires more than a superficial engagement with the information in the frame.

The film is pockmarked by various overtly experimental inserts that are shot with low-definition mobile phone cameras. They capture religious rituals, climate devastation or inconsequential acts of human tenderness which, to Malick, are utterly momentous in the grand scheme of things. These small, tender moments are the director’s moving gesture towards the now, and are his way of linking contemporary viewers of the film to the vast, incomprehensible maelstrom of existence giving birth to itself.

There s a fun game you can play while watching the film, as a few of the shots used can be seen in other nature documentaries. Consider the kobudai wrasse (aka the Asian sheepshead wrasse). It is found in Japanese waters and is known for being able to switch gender at will, and has featured in BBC’s Blue Planet series as a sea-life parallel to questions of human gender identity. As seen in Voyage of Time, the wrasse makes for a figurative example of omnipresent motherhood, and the way life naturally bends towards the staples of preservation and multiplication.

Perhaps the film also offers a vision of existence which is powered not by procreation but asexual reproduction, where beings and organisms just multiply and expand. I finally cracked and forced my mother-in- law to watch Voyage of Time and reader, she liked it.

Song to Song

“There is no safe investment. To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal.”

– CS Lewis, ‘The Four Loves’

The confession that opens Terrence Malick’s Austin-set 2017 film Song to Song points to the desperate emotional malaise experienced by Faye (Rooney Mara). Her desire to make a connection pushes her to extremes. “I went through a period when sex had to be violent. I was desperate to feel something real. Nothing felt real. Every kiss felt like half of what it should be. I was just reaching for air,” she sighs. Rudderless, she pursues a relationship with successful music producer. Cook (Michael Fassbender), not because she loves him, but because of the opportunities it might afford her as a musician. Cook knows her motivations, though he doesn’t care. There’s a contractual element to their relationship as well as an erotic one, and the sex we see between Faye and Cook is transactional, emotionless. She needs something more.

Faye first meets BV (Ryan Gosling) at a party hosted by her boyfriend. She is listening to her iPod. The pair share a pair of earphones, silently listening to gospel singer LaShun Pierce’s ‘I Know I’ve Been Changed’. She sways gently to the music, smiles softly up at him, searching for a reaction. The music drowns out the party guests milling around them and louder music plays over the sound system. They both know at that moment everything is different; Malick’s choice of song is literal, obvious, playful, but perhaps also suggests love as a higher power. From there on, things start to change.

BV talks. Faye listens. She is charmed by his lack of pretence. They laugh and they smile and reach for one another, kindred spirits whose connection runs deeper than a physical attraction.

“Song to Song polarised audiences upon release due in part to its formal and tonal fluidity.”

In the world of Song to Song, physical intimacy without emotional intimacy leads to self-destruction. Faye pursues her relationship with BV while still dating Cook, who is aware – himself sleeping with other women – and seems amused more than anything by Faye and BV’s blossoming romance. Faye cannot give herself over to what she really wants, or indeed who she really wants, perhaps out of fear, or simply an inability to be truly vulnerable with someone else. She’s always looking over her shoulder. When Cook begins to pursue waitress Rhonda (Natalie Portman) she is dazzled by his grandiose displays of affection – he buys a house for her mother. “You wanted me to be free,” she says, but the words don’t match up to the reality. The distinct inequality within their relationship results in ruin.

A non-romantic love pulls BV back home to his family, away from the world of reckless excess that exists in Austin. Discussing their ailing father, his brother asks “Do you think about forgiving him?” “No,” replies BV. “Do you pray for him?” “Not any more.” Yet he still returns home to care for him and provide for the family, such is the strength of their bond; familial love creates a sense of empathy than endures, despite hardship and hurt. Similarly, advice given to Faye by legendary musician Patti Smith drives her to finally allow herself to be vulnerable. “Fight for him,” she tells Faye. “If you really love him, don’t let him get away.” So Faye follows where BV goes, away from the dreams they chased in the city, to a rural idyll. To somewhere as pure as their affection – that “something real” Faye had been searching for.

Song to Song polarised audiences upon release due in part to its formal and tonal fluidity. It mimiks the dreamy, often non sensical nature of love itself, the film is content to focus in on the minutiae of human lives, lingering on the half-conversations and passing glances that we forget within a moment of their occurrence. Malick’s great gift in Song to Song is being unafraid to focus on these seemingly unremarkable details, on all the ways love makes us vulnerable; on its capacity to drives us to self-sabotage or change our lives beyond recognition.

“These rhythms, discordant or harmonious as they may be, are at least honest”

The grand secret we all know but dare not speak aloud is that oftentimes love – in its many splendid forms, between parents, siblings, friends, lovers – can be boring, or trivial, or self-indulgent. Love can be cruel, and immature; it is not solely patient or kind, as the ubiquitous psalm recited at so many weddings would have us believe. But what is life without love? What is life without music? These rhythms, discordant or harmonious as they may be, are at least honest.

A Hidden Life

You don’t have to be devoutly Christian, or even remotely religious for that matter, to appreciate the chief theological concerns of A Hidden Life. But while Terrence Malick’s stirring sacramental epic can be distilled to the fundamental struggle between faith and fascism – good versus evil – the spiritual conflict at the heart of the film is less straightforward. If an air of fatalism hangs over this World War Two-set drama about an Austrian farmer executed for refusing to fight for the Nazis, it is augmented by the director’s constant grappling with the finite nature of existence and the delicate balance between all living things.

Before 2011 ‘s The Tree of Life, urban landscapes had hardly figured in Malick’s cinema; his allegorical tales are almost always foregrounded by nature. In A Hidden Life this manifests as a dreamily idyllic Alpine village called St Radegund, where Franz and Fani Jägerstätter (August Diehl and Valerie Pachner) live and work in uncomplicated harmony with their natural surroundings. But the Jägerstätters’ closeness to God is not only established through their geographical proximity to Him.

“their immutable bond is emphasised by natural light cascading through open doorways, prison bars and the gaps in the wooden boards of a barn”

After Franz is torn from his family, we witness the seasons slowly change while this once peaceful community comes apart at the seams. Yet even when the situation at home reaches its lowest ebb for Fani – her meek, misguided neighbours pouring vitriol on her as she toils in the frost-bitten fields – there’s a sense that she and her two young girls are being looked over, protected by a force infinitely greater than that which has ensnared her husband.

Here as in The Tree of Life the use of floating Steadicam (Jörg Widmer promoted from camera operator on 2017’s Song to Song in the absence of Malick’s regular DoP Emmanuel Lubezki), particularly during the St Radegund scenes, suggests the presence of a divine observer. Symbolically, too, the film is lit in such a way that a warm glow seems to envelop Franz and Fani whether the sun is shining directly on them or not.

“the eternal connectedness of all things – not only Franz and Fani to each other but to every other character in the film”

Even when the couple is separated their immutable bond is emphasised by natural light cascading through open doorways, prison bars and the gaps in the wooden boards of a barn.

The combined effect of these aesthetic choices subtly reinforces the eternal connectedness of all things – not only Franz and Fani to each other but to every other character in the film, to their immediate environs, to God, to the audience, and to the entire span of human history.

It has been argued that A Hidden Life makes a martyr of its protagonist (the real-life Franz was officially beatified by the Catholic Church in 2007), but I don’t see it that way. The film’s title is taken from the final paragraph of George Eliot’s ‘Middlemarch’, which appears on screen before the end credits: “The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

This is basically a more poetic way of saying that not all heroes wear capes; ordinary people are capable of showing extraordinary courage and grace without necessarily seeking validation or recognition for their actions. If Malick believes that God’s kingdom exists right here on Earth, then he also recognises that perhaps the most tragic paradox of the human condition is that our capacity to love is often obfuscated by our inclination towards destruction.

There’s a scene in 2015’s Knight of Cups in which a priest says that God, “shows his love not by helping you avoid suffering, but by sending you suffering… That’s a gift more precious than the happiness we wish for.” When it comes to the Big Questions – the meaning of life and all that – I have always maintained an agnostic position, yet on some level I admire those who are able to keep a healthy covenant with God in a world filled with so much suffering.

That Franz was prepared to suffer and ultimately sacrifice himself despite being given every opportunity to swear an oath of loyalty to the Fiihrer is testament to the absoluteness of his faith. It’s telling, however, that Malick returns to St Radegund in the film’s final frames to show us in full, unambiguous widescreen glory exactly what it is he died for.

Thank you to everyone who contributed to this article. The Last Planet is set to be Malick’s next project.